The colours most commonly used and widely respected among Tibetans are white, blue, red, yellow, and green. These five colours symbolize the origins of the Tibetan primitive religion Bon. In this context, white represents clouds, red signifies fire, yellow denotes earth, and green corresponds to water.

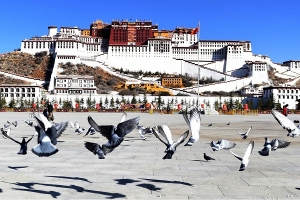

Colourful Buildings in Tibet

The Meaning of the Colours

Yellow is associated with prosperity and symbolizes land. In Buddhist tradition, the Baosheng Buddha, associated with the south, is represented in golden yellow. Consequently, in Tibetan Buddhist paintings, the south direction of the sand mandala is depicted in yellow. The Gelug Sect, one of the five major sects of Tibetan Buddhism, also uses yellow prominently, as seen in this sect’s cassocks and monk paintings. In Tibetan opera, the yellow mask signifies the great virtue of eminent monks.

Yellow is often viewed as a symbol of nobility and typically holds a fixed symbolic meaning. Stone yellow, a mineral colour used for yellow pigment, is significant for religious items and Buddhist clothing, particularly for the garments and rooms of eminent monks and living Buddhas. As a result, ordinary monks and laypeople typically do not wear yellow. Additionally, yellow is not used in residential buildings within Tibetan regions. It serves as a colour symbol for the Yellow Sect.

In Tibetan Buddhist art, the golden colour found on Buddha statues, temple domes, thangkas, and murals is created through traditional gold-melting techniques performed by artisans with generational expertise. Pure gold is specially processed for painting, while gold powder can be applied or fashioned into thin gold foil and adhered to various surfaces. Another method, known as “fire gold plating,” involves dissolving gold powder in mercury, applying it to a surface, and heating it to evaporate the mercury, leaving behind the gold layer.

Tibetan Golden Palace

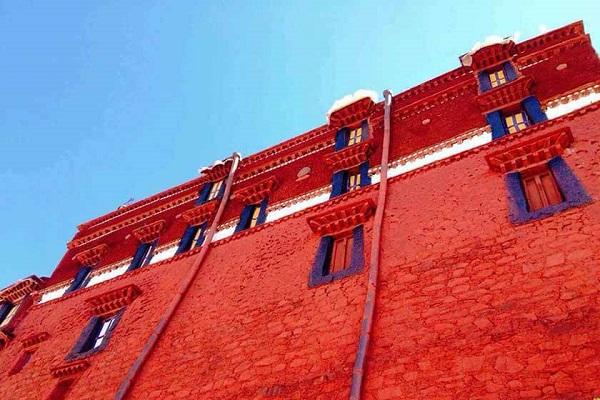

Red, in contrast, is perceived differently in India, where Buddhism originated 2,500 years ago. It is regarded as a common and unobtrusive colour used in monks’ attire to signify detachment and the pursuit of spiritual perfection rather than external appearance. This choice aims to minimize distractions and enhance focus on Buddhist practices. Red has also become a colour associated with eminent monks, monasteries, and temples.

The red seen in Tibetan architecture is possibly linked to the primitive “Bon” religion, which is indigenous to the region. The Bon tradition divides existence into three realms: gods, humans, and ghosts. Historically, Tibetans believed that applying ocher red dye to their faces could protect against ghostly influences. While the practice of face painting has evolved over time, the use of red remains evident in architectural contexts.

Red wall in Tibetan Palace

Blue is significant in the context of the sand mandala, representing the middle position. The blue Immovable Tathagata Buddha holds directional importance in Buddhism. In Tibetan opera, a blue mask denotes the role of a hunter. In addition, navy blue cloth is commonly used in auspicious patterns found on Tibetan door curtains and tents, particularly in rural areas and towns characterized by Tibetan culture, symbolizing auspiciousness and abundance.

Navy blue is predominantly utilized to depict various angry gods and protector gods in religious-themed thangkas and murals. This colour effectively conveys these deities’ power, majesty, and temperament, often enhancing the three-dimensionality of the depicted scenes. The hue also contributes to the overall impact of the artwork.

Blue Deity in Tibetan Painting

In sand mandalas, the east is represented by the colour white. This corresponds to the white Vajrasattva, which holds directional significance in Buddhism. In Tibetan opera, white masks are associated with male characters. Additionally, older adults often wear a white top featuring sun and moon patterns during their zodiac year. This practice is considered to symbolize good luck.

Milky Roof of Tibetan Building

The colour green represents the north direction in sand mandalas. This aligns with the green Amitabha Buddha, which also has directional significance in Buddhism.

Green Decorations in Tibetan Palace

Tibetan Traditional Colour Usage Habits

The Tibetan people on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau have developed a distinct understanding of colour through their long production and daily life history. This understanding is evident in Tibetan architecture and painting, where colour usage conveys a notable “Tibetan flavour.” This article analyses the characteristics of colour application among the Tibetan people, focusing on their traditional practices.

Tibetan art has evolved into a form that exhibits unique national and regional characteristics, influenced by artistic elements from India, Nepal, and the Central Plains of China. This interaction has resulted in diverse expressions and significances within Tibetan art. It retains elements of the original ecological context and possesses a unique vitality. Additionally, Tibetan art serves as a symbol that encapsulates national beliefs and human emotions, reflecting connections to broader Chinese cultural traditions while conveying the Tibetan people’s specific artistic style and identity.

Colourful Traditional Tibetan Dressings

The Extension of Tibetan Colour Art

The extension of Tibetan colour refraction demonstrates distinct characteristics that set it apart from the art of other ethnic groups. This aspect of Tibetan culture encompasses various forms, including thangkas, murals, architecture, sculptures, and folk crafts, all of which showcase the artistic application of colour within Tibetan art. These elements reflect the broader cultural practices and aesthetics of the Tibetan people.